When I worked at Rolls-Royce, I guess because I was perceived by my bosses to be the person most open to ‘weird’ ideas, I was the nominated person to receive the letters occasionally sent to the Company from individuals claiming to have re-invented the jet engine. They averaged one or two a week. Meaning that, after a few years, I’d had the pleasure of reading several hundred suggestions. After the first few dozen, my initial excitement had begun to diminish. The ideas were already falling into what later became two distinct categories. The first came from the person that had not thought to check on whether someone in the industry had already thought of the idea. The second, depressingly more frequent category, came from people that didn’t understand the basics of how the world works. Things like physics, Bernoulli’s Equation, the Laws Of Thermodynamics, and gravity. Don’t get me wrong, my mind wasn’t and still isn’t closed to the possibilities of breaking some of these Laws (I’ve done it successfully myself on a couple of occasions), but there ought to at least be an attempt to understand them first. Needless to say, in all the time I received and responded to these approaches there was not a single occasion when anything tangibly useful appeared. Nothing even close. The ratio of bad-to-good was infinite. It was like Open Innovation before Open Innovation existed.

These days, we still get some of these kinds of approach from people. Only now it’s a cornucopia of things rather than just perpetual-motion-powered jet engines. Mainly, though, I get to meet people in client companies that find themselves in the same role I had at Rolls-Royce. Only now times have changed. Firstly, they tell me, the flow rate has increased considerably. Secondly, the level of in-company paranoia has increased exponentially. No-one wants to be the person that turned down the Beatles.

It only takes one or two cases for this paranoia to become extreme. The knowledge that Hoover turned down Dyson, for example, when he approached them with his cyclone vacuum cleaner. As it happens, I met several times with the person at Hoover who did the rejecting. He insisted he would do the same thing again tomorrow. I could empathise with him. Even after the fact I’d approached the company in pretty much the same way Dyson had, only with a far better way of cleaning floors than a cyclone. But that’s another story.

Spool forward a few years to 2010 and a client asked us to get involved in the emerging Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf Of Mexico. The client wasn’t BP or a competitor of BP, but rather someone interested in Open Innovation. Which, thanks to Henry Chesbrough’s 2003 book had already become a thing. A shiny bright dysfunctional thing. Our brief was to watch what happened when BP decided to embark on their own Open Innovation experiment. The Deepwater Horizon oil-spill was an almost impossible to solve problem. Thinking it would help allay some of the already horrendous public relations damage caused by the incident itself, someone at the company figured, ‘let’s tell the world what the problem is, and lots of people will turn up with answers’. 300,000 responded within the first week. Humans love a crisis. Especially when the crisis belongs to someone else and we have no skin in the game. Humans love to help.

Pity the fool, though, that had to work their way through those 300,000 suggestions. 299,999 of which were very likely to have come from the knowledge-vacuum person who took time out of writing to Rolls-Royce to explain how to re-invent the jet engine.

Frankly, you need a small army of people to go through that many ideas. A small army that BP clearly didn’t possess. So, less than two weeks after the call first went out, the media started to hear from some of the call responders. ‘I told them what the answer was, but they haven’t listened,’ was their clear message. Something done, I’m sure, with the best of intentions had quickly turned into a PR disaster. If it hadn’t been for the BP CEO, Tony Hayward, committing the all-time worst PR blunder in history, its possible that BP could have killed the Open Innovation mess for good.

Thankfully for Henry Chesbrough, but not so good for everyone else, Open Innovation survived Deepwater Horizon, and Chesbrough got to spread his naïve, ill-conceived claptrap even more broadly.

Which brings us to the Covid-19 pandemic. This time a global crisis that has already, just weeks in, shown everyone the human spirit in all its manifest forms. The occasional profiteer – who, one of the best things to come out of the social media echo-chamber-creation machine, have been universely called out for their evil ways – but mainly the literally millions of people wanting to help. Simultaneously heart-warming and utterly chilling.

When half a million Brits answered a call to volunteer to help out the NHS, that’s the heart-warming part. Volunteering to deliver prescriptions, help prepare food and do portering jobs, we see humans quite literally at their community-minded finest.

But then, on the other side, oftentimes the ‘help’ ends up being the precise opposite. We’ve been asked to work on a couple of the emerging bottleneck problems – ventilators and masks. The world doesn’t have nearly enough of either. Both problems are serous, but the ventilator shortage is the most life-threatening. Not surprisingly, many public officials started to put out calls for more ventilators. A classic Open Innovation play.

Finding technical solutions to both problems has been easy. That’s what happens when you have a method. The real issue, we predicted, is going to be fighting through the noise. We’ve already seen some of the consequences of this in the UK. Big, sexy ventilator contracts offered to (Government supporting) Dyson on the one hand, and a small company that already makes ventilators being ignored on the other. The sort of state incompetence both Orwell and Kafka would have rejected as too far-fetched.

We’re back in Deepwater Horizon territory here. Only this time hundreds of thousands of human lives are at stake. Tens of thousands of helpful – jet-engine re-inventing – souls that are clogging up the system with naïve, time-wasting crap. Worse still – like Deepwater Horizon – many of these people are precisely the same highly opinionated ‘geniuses’ that will soon be going to the media to moan about how they aren’t being listened to. Thus compounding the problem even more. Not only are those in charge wasting time ploughing through hundreds of nonsensical ventilator rescue suggestions, but now also having to justify to the press why they haven’t responded to all the amateur Professor Branestawm wannabees.

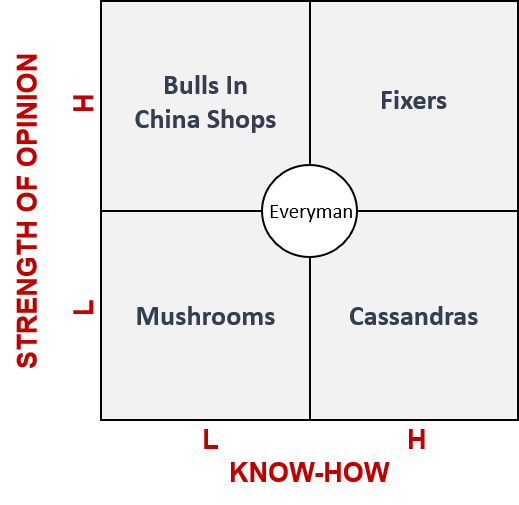

Strongly opinonated people are really important in an innovation context. But only when they have the know-how to back it up. The world doesn’t have enough of these know-how-and-opinion ‘fixer’s right now. Meaning we end up with a million and one bulls in the ventilator shop and a growing number of Cassandra’s, pulling their hair out with frustration at the lack of attention they’re getting. In normal times, the cream has time to rise to the surface. In crisis times, tragically, wrong answers thrive while the needed answers wither on the vine.

Not that its for me to make any kind of public plea, but if I could, it would to politely request that those beautiful people that want to help, but have no relevant know-how should stop clogging up the communication channels and stay out of the way. Go do the shopping for the locked down vulnerable members of the population. Grow some vegetables. Volunteer to help farmers pick crops. Save lives, stay home, shut up. Let those with the actual knowledge – the quiet ones, the Cassandras – do what society now needs them to do. This is their time.