I’ve written several times now about the idea of every aphorism having its equal and opposite analogue. What I haven’t worked out yet is whether they all therefore ultimately cancel out – a zero-sum feast of smart sayings – or whether they lead to some kind of higher truth. A truth emerging from Hegel’s dialectic method of progress that postulates a higher level proposition synthesised out of a reconciliation of a conflict between thesis and antithesis. I guess I was hoping that someone would pick up the challenge and that, one day, I’d receive the definitive dissertation in the mail. Sadly, still nothing has arrived.

Which I guess means that if there is an answer out there, I’m going to have to be the person that does the hard yards required to find it. Damn.

So, in true, how do you eat an elephant fashion, here’s what I hope will become a series of bite-sized attempts to try and synthesise something meaningful from pairs of opposing aphorisms.

Here are two of my simultaneous favourites:

“When the pressure is on, you don’t rise to the occasion – you fall to your highest level of preparation.” Chris Voss

“To achieve great things, two things are needed; a plan, and not quite enough time.” Leonard Bernstein

The underlying physical contradiction between Voss and Bernstein centres around pressure: Voss’ thesis is that pressure is basically bad, while Bernstein’s is that, by not quite giving ourselves time to do a job, the resulting pressure is good. Can both be right? Can we construct a picture that allows both aphorisms to hold true?

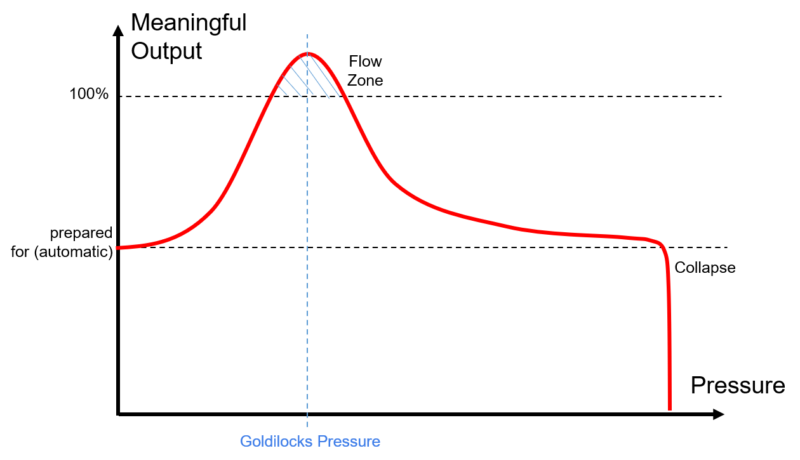

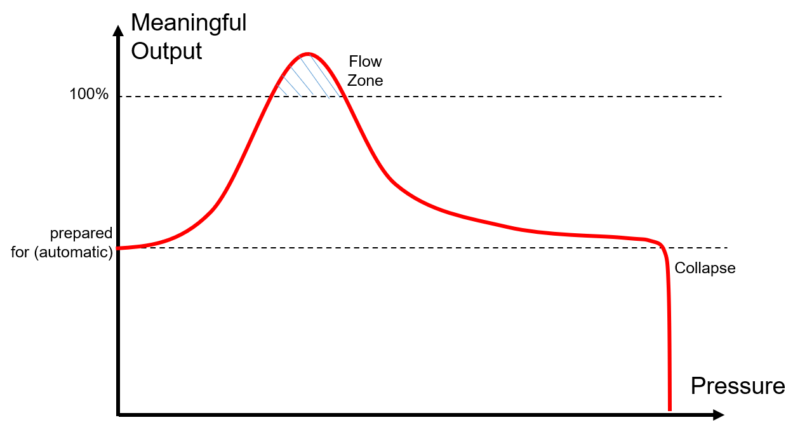

I think so. I think it looks something like this:

The upshot of which, I believe, is that both esteemed thinkers are indeed correct. Provided we understand the varying impact on outcomes attributable to varying levels of pressure. To Voss’ point, if we put too much pressure on people, they stop thinking, and hence revert to ‘automatic pilot’ (plus, if we keep increasing stress sufficiently, we eventually cause a cliff-edge collapse). To Bernstein’s point, if we put people under ‘Goldilocks’ conditions (i.e. just the right amount of pressure), we can attain a one-plus-one-is-greater-than-two level of output. Getting the level of pressure right allows people to enter a ‘flow’ state in which their creative juices come to the fore and difficult problems get solved.

I’ve deliberately used the idea of achieving ‘more than 100%’ outcomes in the figure, knowing that I regularly encounter individuals who become very uncomfortable at the thought. I have some sympathy with their view. Usually, when I hear naïve Millennials (yes, it is still possible to be extremely naïve when you’re in your late thirties) claiming they’re going to put ‘110%’ into their next relationship, or that they’re committed ‘120%’ to the project goals. Most times when people say these things they’re merely regurgitating a modern-day trope and don’t know what they’re talking about. But occasionally they do. In the jet engine business, for example, engines are designed to have a series of different power ratings. One of which is ‘100%’. This is the maximum level of power the engine is designed to be able to deliver continuously over the entire scheduled life of the engine. The jet engine industry being very safety conscious, its also standard practice to recognise that in some situations an engine might fail unexpectedly – e.g. by ingesting a wayward goose. If an aircraft loses an engine, the other engine(s) are then able to be operated at power levels greater than 100% to compensate for the power lost from the non-functioning engine. These higher power levels – in extreme cases 160% – can’t be sustained indefinitely, but they can be used for long enough that the aircraft can either safely return to the ground or, more usually these days, fly for several hours to reach the intended destination. At which point the over-exerted engine will be inspected and its remaining life re-calculated.

Exactly the same ‘extreme situation’ capability is available to humans. We are usually calibrated to be able to work a 40 or 50 hour week (120 if you’re a Systematic Innovation person). Whatever our normal week looks like, that’s our ‘100%’. We also know, I think, that occasionally we’re able to go beyond the 100% level. The ‘all-nighter’ to submit the final report for example, or the ‘hackathon’ to solve a knotty problem. The key point being – like in the jet engine – that we do it for a short period of time and not (as some employers seem to think) for ever.

I believe many individuals instinctively understand this ‘more than 100%’ capability. We take advantage of it when, like Bernstein, we deliberately don’t quite leave ourselves enough time to finish what we’ve been tasked with. Back to the figure again, if we get the pressure level ‘right’, we get to take advantage of a flow-based synergy effect.

And maybe that’s the higher-level synthesising third-aphorism takeaway from Voss and Bernstein’s apparently contradictory quotes: if we manage to hit the Goldilocks pressure level, we win, if we miss it, we get what our automatic pilot is prepared for. Or collapse.