Now we live in a world of constant coronavirus testing, the question of how to make a step-change improvement in testing rates arises.

Back in November, a group of Israeli scientists announced their method for revolutionising testing protocols in a hospital lab, with a change they say can instantly quadruple the capacity of almost any coronavirus screening facility in the world.

Systems immunologist, Professor Tomer Hertz announced that the lab at Soroka Medical Center in Beersheba would be shifting immediately to the new strategy.

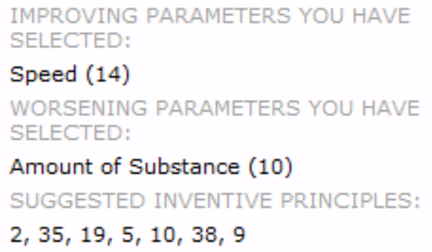

From a TRIZ perspective the test-rate problem represents a simple to describe contradiction. Namely that we want to improve speed, and the number of tests required to be analysed prevents us. Here’s what the Contradiction Matrix has to say about the problem:

And the Soroka Medical Center solution? The change isn’t powered by a medical or technological innovation, but rather by some cleverly applied mathematics. Labs will use only their regular computers and widely available machines to implement the solution. Which, in classic ‘blinding flash of the retrospective obvious’ involves testing in batches. The normal impediment to such ‘pooling’ solutions is that they are logistically clunky and require a two-stage process. The minority of labs that currently “pool” samples combine the RNA from several people and test it as if it were a single sample. Then, if a positive result is detected in the batch, each individual sample is retested to see who generated the positive result.

The new method eliminates this two-stage approach, telling lab workers exactly who is positive from the initial “pooled” test.

It is the brainchild of Open University computational biologist Noam Shental. Or rather, in a sense, his mother. In March she reminded him during a family lunch that a decade ago he had developed a pooled method to test sorghum, a flowering plant from the grass family, for a genetic disorder, and urged him to repurpose the research for coronavirus in humans.

Shental started thinking through the maths on the drive home, and quickly got Hertz and another Ben-Gurion professor, Angel Porgador, on board to do exactly as his mother had said.

The basis of their method is that a range of “pools” is prepared in a lab at once, and RNA from each sample is added to several of them, often around nine. “What happens then is that we ‘read’ the pools,” said Hertz. “This means that we look at the pattern of which pools showed positive results, using a modified version of the sorghum calculation, which tells us exactly who is positive.”

“Unlike in regular pooled testing, there’s no need for us to reexamine samples from pools that tested positive in order to pinpoint exactly who is positive. We already know.”

From a contradiction-solving perspective, the solution offers up an elegant illustration of Inventive Principles 5 (Merging) and 10 (Preliminary Action).

From a more general perspective, the Covid-sorghum connection offers an iconic example of the more general TRIZ philosophy of ‘someone, somewhere already solved your problem’, albeit the ‘someone’ in this case was the same person. Just ten years earlier.

Thirdly, and perhaps most important of all, the case offers up a timely example of the emerging Covid-sparked Crisis Period innovation paradigm. First, Covid-19 triggered the arrival of a host of expedient testing solutions, and now we see the frustrations associated with those initial solutions provoking the true innovation.