It feels like my list of rules-of-thumb is growing. If someone asks me a question that piques my interest, it’s highly likely – assuming we (the SI research team) are able to reach a sensible looking answer – to generate a paper or an article or a blog post. If someone asks me a question that doesn’t pique my interest it gets filed. Filed until about ten people have asked the same question. At that point I feel I should probably do something. The question probably still doesn’t interest me, but the fact that multiple people have thought to ask it very likely does. I think this rule of thumb has kind of always been there, I just never explicitly thought about it. Maybe that’s a lockdown effect? Too much reflection time. Or maybe just lots of locked-down, bored people asking random questions?

Anyway, this week’s ten-time question concerned aesthetics. And specifically, is ‘make it beautiful’ a 41st TRIZ Inventive Principle?

Before I get too much further, probably best provide the one word answer up front. No.

That’s not the interesting bit.

In relating Principles to ‘beauty’ it is necessary, I think, to divide the story into two segments. One in which beauty is the solution, and one in which beauty is the problem.

Let’s start with the latter. One way of thinking about ‘beauty’ is that it is one of the desirable outcomes of some form of (human) activity. If we are seeking to achieve beauty, the question becomes, ’how do we do it?’ Taken from this perspective, the Inventive Principles offer up the full spectrum of possible ways to achieve what we are looking for. They are provocations and directions that will eventually (if we are persistent enough) give rise to beauty. In this sense, any of the 40 could do the job. From personal experience, and looking at the technical version of the Contradiction Matrix – where ‘Aesthetics’ is one of the Improving Parameters – we know that some of the 40 Principles are more likely to help deliver ‘beauty’ than others. Simple example: Principle 4, Asymmetry is frequently obervable in a photography context as the ‘rule of thirds’ – i.e. an image ‘looks better’ if it is not in the centre of the picture but rather is shifted so it is centred around one of the ‘third’ lines.

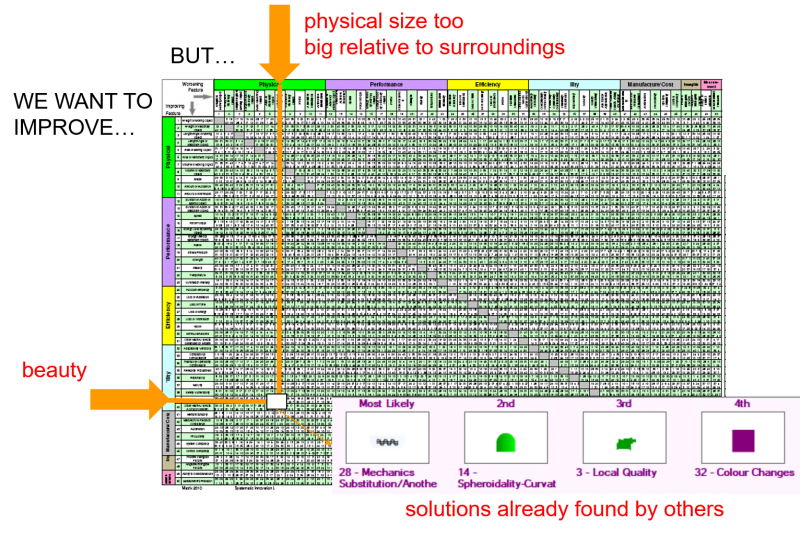

Or, by way of a classic architecture contradiction, the architect always seeks to make the buildings they design ‘beautiful’, but they also know that beauty can only be achieved in the context of the surrounding structures. Here’s what this problem might look like when mapped onto the Matrix:

At this point, the Matrix offers a ranked list of the most likely beauty-delivering solution strategies. So far so good.

The other way of thinking about beauty in the Principles context, then, is that it is the solution to a higher level contradiction. So, for example, I might have a contradiction formulated as something like, ‘I want to improve customer revenue, but my solution needs to be very cheap to produce’, look that up on the Matrix and be informed that ‘making it more beautiful’ would be a good solution direction to go and explore. It worked for IKEA I suppose.

In this scenario, IKEA aside, there is a case that ‘make it beautiful’ is a valid solution provocation. Taken in this context, the question becomes whether it justifies a separate Inventive Principle provocation of its own. In my view, the existing Principles already do the job as well as they need to. At least in a generic sense. Principle 38 kind of implies it. So do 16 and 17. But then Principle 35 becomes the real ‘get out of jail free’ card in terms of why ‘make it beautiful’ cannot be a 41st Inventive Principle – ‘Parameter Changes’ is a very (very!) general Principle and so covers a myriad directions.

Over the years, I’ve tried to get the TRIZ community to rethink the Principles. With, of course, zero success. Unless triggering angry emails from TRIZniks counts. Anyway, if I could, Principle 35 is the first one I’d look to change. When the chronologically generated Soviet list of Principles had grown to 34, I’m pretty certain that Altshuller and team looked at all the miscellaneous unclassified solutions that they’d accumulated, looked at each other, and asked themselves, ‘what do we do with these?’ And then, because no-one could come up with a good answer, they collectively shrugged their shoulders and said, ‘screw it, let’s just bundle them all together and call it ‘Parameter Change’. And so Principle 35 became this awkward hotch-potch orphan. The embarrassing relative we always seem to get stuck with on family occasions.

The best we’ve been able to do to solve this Principle 35 rag-bag problem is to do technical, software, business, architecture. Literature, etc versions of Principle 35 (with it’s A, B, C, etc sub-variants) so that it becomes more useful as a solution generation provocation than merely .’change something’. In this context, I have also suggested to almost everyone that I meet during workshops that they should make their own list of the 40 Principles, adding their own examples. Things that are meaningful to them personally. Which, if it makes sense in your specific context, might well include examples connected to ‘making it beautiful’ as a solution direction.

Meanwhile, for me personally, I know that if someone suggested ‘make it beautiful’ as a solution direction, I’d have two reactions. Number one, I’d think that any solution creator in any domain that is worthy of the label ‘creator’ already knows that aesthetics and beauty are a part of their job. Asking this person to ‘make it beautiful’ is about as useful as suggesting they make it ergonomic. Or long-lasting. Or any other trite statement of the obvious. Yes, I know, there are a lot of ‘creators’ out there who are not worthy of the label. ‘Helping’ them by giving them facile reminders of their job, sadly, does nothing to increase the likelihood of achieving a beautiful solution. The solution will still look rubbish because the creator was rubbish.

Second, and more important, comes the next level problem down the hierarchy. As soon as I remember that aesthetics are important and that I need to achieve something that is beautiful, there is very likely to be a dawning realisation, as i dig deeper into the details of the design, that my desire to create beauty is hindered by my parallel desire to improve another design feature. And at that point – realising that achieving beauty is the problem – all I need to do is reach for the Contradiction Matrix in order to tap in to the solutions of tens of thousands of better creators than me, and stand on their shoulders.